The Orphanage Controversy

Q: Your novel is dedicated to the voiceless abandoned Chinese babies and to your father, who “taught you that parenting is not biology?” What is the story behind this latter dedication?

A: My very special heart father. He married my mother when I was eight, and it was an instant bond between us. We started talking at our first meeting and never stopped for thirty-five years until his death. You can read about our strong connection in my personal essay about him, My Heart Father.

Q: It’s quite a fictional leap to the story of CHINA DOLL.

A: I bring with me the overriding emotion to each of my novels. The rest of the seeds for this story came from nuggets of material culled from different impressions. For starter, I never felt that the bond I’ve forged with my first daughter was a result of the pregnancy and child birth. I would have loved her just the same had someone dropped a baby into my arms. China was a place where such a thing could happen.

Q: Wasn’t abandonment of infants in China your starting point?

A: It was on my mind, but climbing a soap box is anathema to writing suspense fiction. However, when I went to Beijing in 1995 to explore the details of this nascent story, the facts of this human tragedy hit me full force. I couldn’t turn my back on the 1.7 million abandoned and killed baby girls each year.

1995- Talia interviewing old Chinese women

Q: How did the two world superpowers—the U.S. and China—enter the picture?

A: My passion in writing is to explore the forces that shape our lives-political machinations, big government, the legal system. They intrigue me with the infinite possibilities in which the human spirit can either be broken or rise above them. I also enjoy entering the skin of a character from a different time, place, genre or cultural background and letting him or her speak, act and think through me. CHINA DOLL is populated with a host of characters whose emotional landscapes are remote from my own.

Q: But not motherhood. That’s seems to be the theme in your novels.

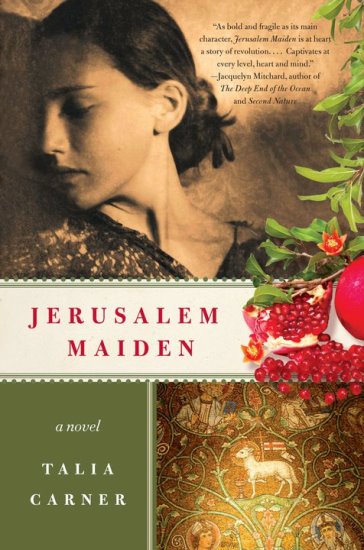

A: Motherhood has been the most powerful fuel of my adult life-even as I had to overcome obstacles in the pursuit of my career and have enjoyed a great love marriage. However, in my next novel, JERUSALEM MAIDEN, I am exploring a different angle of this very same human experience.

Q: Why did you choose a music icon as your heroine?

A: The pressure cooker of an artist’s life makes her decision to rebel so much harder. There is a whole industry around such a person, dozens of people whose livelihood directly depends upon a star. She is bound to them. She has less freedom to change her life or break loose. She is subject to the agendas of people closest to her. How easy is it for them to become her enemies? In CHINA DOLL, Nola Sands has been the culprit in losing her freedom to choose and to act independently. She would need to climb out of this hole in order to save Lulu.

Q: Did you travel to China? How did you do your research?

A: I participated in the 1995 International Women’s Conference in Beijing, and afterward traveled for a few weeks in the countryside, where, over my jars of peanut butter, I spoke with women-university professors, industry directors, aging farmers, and budding entrepreneurs-about their customs and apprehensions. I learned that generation after generation, due to either lingering starvation, the social experiment of the cultural revolution, or the current sacrifice under the one-child policy, women in China have been losing their baby girls through coercion, prejudice, neglect—and outright murder.

I also gathered the flavor of China, its smells, sounds and tastes, which are like nowhere else in the world. Yet, being so close to the place and its dynamics made writing this novel overwhelming. In the next three years I wrote another novel, PUPPET CHILD, and only after it was finished, was I ready to tackle this project. I proceeded to attend lectures and to interview officers of the U.S. National Security Administration, State Department, CIA and Foreign Service to better understand the U.S.-Sino relationships. When no travel agent would send me to the dangerous area I wished to cover, I watched documentaries and studied the geography of the terrain, including the fauna and flora. I spoke with Chinese-Americans to catch the nuances of speech and thought process.

Q: Would you please explain the population crisis in China?

A: In China, 22% of the world population lives on 7% of the arable land. At 1.3 billion people-and still growing until 2014 when the growth is hoped to level off due to the one-child policy-the danger of population explosion is a serious issue that threatens the return of China’s pre-Communist days of famine. To put the population size in perspective: the U.S. has only 6 cities with more than one million people, China has more than 60, yet the majority of its population lives in rural areas! Had each couple been allowed to have two children, we would see China doubling its size to 2.6 billion people!

Q: What is the one-child policy? How does it affect Chinese families?

A: In 1979, the Chinese government initiated a policy that permitted only one child per couple. As a result, China now sees a second generation of single children in a family with no aunts or uncles, no siblings or cousins. Instead, two sets of grandparents and one set of parents dote on the one child, aptly named “Little Emperor.” The Chinese maintain a strong tradition of preference for boys; girls are called “maggot in the rice” and often aren’t even named. (They are often numbered as Girl 1, Girl 2, etc.) Many parents opt to have a boy because in rural areas, a boy farms and takes care of his aging parents; China offers no other old-age benefit program. A girl, on the other hand, goes to live and serve her husband’s family and is therefore considered a waste.

1995- Talia at her graduating ceremony of Cultural Exchange in Hungzhou

Q: Who imposes the policy?

A: Many Chinese live in rural areas or in urban “work groups” that provide housing, education, jobs and social services. If a couple tries to keep a second child-or even has their one child born in the wrong year of the quota-the work-group’s administrators or the community leaders exercise severe punishments that include loss of jobs and social benefits, ostracism, imprisonment—and even house burning and beating!

Q: What are the social consequences of the one-child policy?

A: When juxtaposed against the deeply rooted Chinese preference for boys, the dire consequences of this policy is that there is an estimated ratio of 120 boys to every 100 girls (compared with the global ratio of 103 boys to 100 girls)—and some regions have documented 6 boys to every girl! This means that each year, 1.7 million girls are either aborted, killed soon after birth, or die before age 5 from deliberate malnutrition or medical neglect, as parents do not extend the same care to girls as they do to boys. It is estimated that 60 million men in China now cannot find a bride, a situation that leads to kidnapping, trafficking, and forced marriages.

Q: Is there a conflict between U.S. and China?

A: Experts claim that they are on a collision course for world dominance. China’s agenda is to become a superpower; it has already shown desire to control the Pacific Rim. In the meantime, we’ve seen small and large conflicts erupting between the U.S. and China. To rephrase one of CHINA DOLL’s characters, Big Mouth Roberta: “The Los Alamos spying scandal breaks amid a flurry of prior accusations of China stealing military secrets. China’s president, Zhu Rongji, comes to the U.S. to clinch China’s entry into the World Trade Organization. He agrees to all the concessions requested of China-and it costs him at home-but just then the U.S. bombs the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade. No sooner do the Chinese get over the shock, when Taiwan makes noises about independence, and the U.S. sends its Navy to meddle in what China sees as an internal affair. This fracas is not yet over when the U.S. downs a Chinese plane at China’s own coast, while we proceed to protest their sales of missiles to hostile nations.”

And this is only until the year 2000, when CHINA DOLL is set. The problem in this race for dominance is that the Chinese are not bound by our Western values of human rights, freedom of the individual or notions of public accountability. They have no compunctions about threatening their neighbors who may not take kindly to the Chinese view of themselves.

Q: What should the U.S. foreign policy be?

A: There are two schools of thought about the strategies the U.S. must deploy toward China: Engagement vs. Containment. “Engagement” holds that the more channels of communication are open between the two nations, the more it is inevitable that China will transform from a totalitarian state to a democracy. Sixty thousand Chinese students in U.S. universities learn firsthand about freedom and democracy. High-tech factories in China are built and managed by Western firms. And China’s cultural wall is being cracked by Western pop culture-be it jeans or music. “Containment” maintains that China is a dangerous, ambitious nation that must be isolated. China sees democracy as a weak form of government. Their success in influencing top U.S. politicians-including financing the re-election of a president-and the ease with which they have infiltrated both open American scientific institutes and closed military installations are proof that democracy is a failure. As China bides its time, it aids countries hostile to the U.S. but uses the U.S.’s willingness to share its top secrets to arm what is soon to become the strongest military power in the world. Against signs to stay guarded, the U.S. policy is that of engagement.

Q: What are the moral difficulties U.S. corporations face when expanding into the Chinese market?

A: Compromise on human-rights issue and basic Western values. U.S. corporations-and many U.S. legislators in both houses-dismiss the warning to stay guarded. They’re willing to sacrifice global security and human rights-present and future-for greater profits. We’ve already seen how American corporations’ fast expansion into the Chinese market has negatively affected their moral judgment. Yahoo actually gave the Chinese government access to e-mails of subscribers, which put at least two dissidents in jail. Under the Chinese government’s dictate, Google has adjusted its search engine to block thousands of websites. The Chinese military is the country’s largest industrial force and it also runs many prisons, using prisoners as free labor. Some U.S. companies ignore the labor source producing its products in China.

Q: How does China’s communist-regime move into capitalism compare with Russia’s? Are we to see the chaos we saw in Russia in the early 90s?

A: In Russia, capitalism started at the top, even during communism, but did not seep down toward the bottom of the pyramid. When communism fell, the top echelon was poised to grab national resources and major industries. There was no system to stop them as all the infrastructure of law, social services, and administration disintegrated, while no alternate system replaced it for years. In China, capitalism has started from the bottom, as farmers are allowed to sell whatever they produce over their allocated quota. In fact, the growing middle-class Chinese are often farmers who live close to the main cities, where they can sell their produce. The infrastructure of a totalitarian regime has stayed in place-and I can argue that it is not even communism-and there is no indication that it will be dismantled any time soon.

Q: What are the Chinese “orphanages” and The Dying Rooms controversy?

A: According to Human-Rights Watch/Asia 1996 report, there were 40,000 warehouses of old people, disabled and infants, often all living under one roof. The death rate in these institutions reached 80%, the same as in Nazi concentration camps. Since the late 90s, a handful of orphanages-perhaps a couple dozens-have become showcase institutions that supply babies for foreign adoptions. Even in those, adoptive parents are permitted to visit only selected play areas filled with colors and toys. Reports of the other areas of these same orphanages reveal unacceptable practices such as tying babies to their potty seats for hours on end. These showcase institutions were built after a ’95 BBC documentary which coined the name “The Dying Rooms,” the International Women’s Conference in ’95, the above-mentioned ’96 Human Rights Watch report, and the ’97 World Health Organization report of 50 million women “missing” in China because of institutionalized killing. All these reactions made the Chinese government aware that their practices of deliberate neglect leading to death were frowned upon, and it caught China by surprise. Until then, the Chinese government maintained that natural selection should do its work without human interference. Out-of-quota and abandoned babies were ‘surplus population’ to be disposed of. The Chinese were shocked to discover that the West didn’t take kindly to this view. From their point-of-view, they were in fact conforming to the international pressure that had recommended population control in the first place.

Q: Haven’t things changed considerably in the past several years?

A: How we hope that evil disappeared from this world…. In institutions where Western charities have entered, there are huge improvements, for they bring funding, education, equipment and medical care to thousands of babies and children. The Chinese now permits adoptions by American and European families as well as, under certain circumstances, domestic adoptions. I have seen huge outdoor posters encouraging choosing a daughter.

Yet, the fact of 1.7 millions missing girls remains. And we must remember that in the “orphanages,” where there are mostly girls or disabled boys, these babies are not orphans, but rather abandoned by parents! Individually, each couple must have agonized about their indescribable loss. I show that silent pain in a scene in Nola’s last concert in Shanghai. But what kind of a society does that to its baby girls on a systematic basis? On a primal and cultural level, the Chinese mentality hasn’t changed within what is merely a fraction of time in its very long history. It is hard for us, Americans, to grasp with our Judeo-Christian mores the economic necessity that is behind the Chinese preference for boys. Also, it is not within the collective Chinese tradition to cater to individuals’ needs or to heed human suffering. And as China forges ahead in its stellar speed development to catch up with the West, the Chinese government has stated that it has neither the resources nor the inclination to waste on those who can’t contribute.

Q: What about domestic adoption in China? Doesn’t it exist?

A: Of course. Childless Chinese couples are allowed to adopt. Also, there is anecdotal evidence pointing to unofficial adoptions or fostering of foundlings, as humanity shows its strength against oppression. However, the Chinese government does not make it easy: the fees associated with such official adoption of foundlings are often beyond the means of the average Chinese. Most importantly, the fact that such sheltering of abandoned infants must remain unofficial is further evidence of the entrenched policy that doesn’t permit saving these babies. The tragedy is compounded by the fact that these unregistered girls are not entitled to education or medical services, and later in life can neither hold an official job nor move elsewhere, and are therefore doomed to life of illiteracy, poverty and often slavery in the guise of marriage.

1995- Papermaking in China

Q: Your website lists many Western charities that have been helping.

A: Western good intentions and money go a long way. But isn’t it tragic that babies are saved mostly when such a charity gets involved? Foreign adoption agencies have been contributing millions of dollars to improving the conditions in the institutions with which they work. Adoptive parents report that their Chinese daughters have come from good institutions with warm caretakers and that the Chinese parents who had abandoned their girls in the first place had done so in locations that ensured their discovery. Besides the fact that these adoptive parents do not wish to stigmatize their daughters, they are probably right about the better care their daughters received.

Q: Yet, many deny systematic neglect in China. They say that things have changed.

A: The handful of showcase institutions accessible to foreigners are only a few of the 40,000 previously reported. The UK-based COCOA that has been on the forefront of this problem reports the existence of 100,000 such warehouses of human suffering. And where are the older children who have not been adopted? There should be tens of millions of them… The fact is that in rural China, which is about 70% of the country, both illiteracy and traditions are high. Changes of any kind do not happen overnight.

Q: Have you come across information not published elsewhere?

A: In government figures given to me in 1995, “special education” as we know it for the disabled, blind or retarded was given to a tiny fraction of one percent of its population. “What about other disabled?” I asked. “There are no others” was the answer.

The pervasive attitude of callousness toward human life has not changed. A June 2001 Marie Claire magazine featured a story, “A Dead Infant Lying In the Gutter Like Trash,” showing how passersby ignore the dead infant’s body for hours until a man picks it up with a newspaper like it were dog’s poop and throws it in the trash. The story was not published electronically, but it was scanned into my website, and I recently discovered that hundreds of websites are linked to it. In addition, the original web pages of the BBC ’95 documentary titled, “The Dying Rooms” were long removed to be replaced with a milder version titled, “The Return to the Dying Rooms,” but the original gruesome photographs are still on my website. There are chain letters circulating in Europe in Spanish and Italian, linking to these articles on my website.

Q: How come we don’t hear much about any of it in the media?

A: Interestingly, rather than open its practices and institutions to public scrutiny to prove a drastic change, the Chinese government has threatened to turn off the faucet of foreign adoptions should any criticism of its policies and infanticide continue! It has also become more vigilant in preventing anyone from taking a close look, while the American government and foreign adoption agencies have silenced criticism in spite of the fact that circumstantial evidence points to the continuation of neglect and murder of babies all across China, in and out of the “orphanages.”

Even the U.S. Congressional-Executive Commission which is mandated to monitor human rights in China mentions infanticide only in passing—and only in alternate yearly reports.

Q: What are the inherent problems with adopting Chinese babies?

A: Corruption rears its ugly head where money is involved. In November 2005, baby-selling rings were discovered in orphanages supplying infants to the showcase institutions designated for foreign adoptions. American adoptive parents leave behind $3,000-5,000 for each child. The rings have been selling infants to these showcase orphanages at $150 a head. There was talk of these babies having been bought from destitute parents or even kidnapped for this lucrative trade.

Q: CHINA DOLL, though, brings the subject to the forefront.

A: The Chinese government is very cynical. In the past 10 years, China has earned an estimated $100 million from selling babies to foreigners and $80 million from renting panda bears to American zoos. There is a fast trade in “unclaimed bodies of prisoners.” Adoption is an industry, and should be understood in that context.

Q: In December 2006, the Chinese government issued new guidelines for adoption of children by foreign couples, excluding single, gay, over 50, obese, disabled and other potential parents in order to ensure better quality of care for its adoptive babies.

A: There have been no report of unhappy matches between Chinese babies and American parents that I know of. On the other hand, there has been corruption in China associated with foreign adoptions and the windfall of money (only 5-10%, according to one report, benefit the children), and there has been a surge in applications to the point that foreign adoptions have become a trend, which, Chinese human rights activists tell me, require the Chinese government to reclaim control. Making people uncomfortable is a form of totalitarian assertion. According to the NY-based human-rights activist, Dr. Wenyi Wang, humane considerations never come into play in the culture of a Communist regime, and therefore we see no special relaxation of the new adoption rules in regards to disable or older children in orphanages that could be helped by single parents or parents over 50, obese or not.

Furthermore, the Chinese government cannot accept a policy that regards life in a democratic society as more advantageous for Chinese children.

Q: Explain the name “CHINA DOLL.” Isn’t it chauvinistic and racist?

A: Learning of my upcoming novel, a mother of an adoptive Chinese girl wrote me before the book was published, imploring with me to change the name. “Every time someone looks at my daughter and says she’s a ‘Chinese Doll,’ it’s a dagger in my heart,” she wrote. The irony is that the China doll in this novel is not the baby. You’ll have to read the book to find out more.

Q: What do you want readers to take away from your novel?

A: The celebration of the strong bond and unwavering commitment of an adoptive parent toward a child.

1995- Talia at the Great Wall of China