Additional written interviews:

- Mystery Playground

- Deborah Kalb

- Sharon K. Connell

- Sylv’s Author & Film Market Interviews

- Mercedes Fox

- “The Heroine’s Journey”

- Writers Of The World

- Interview by Jasper Kerkau

- Inside the Emotions of Fiction

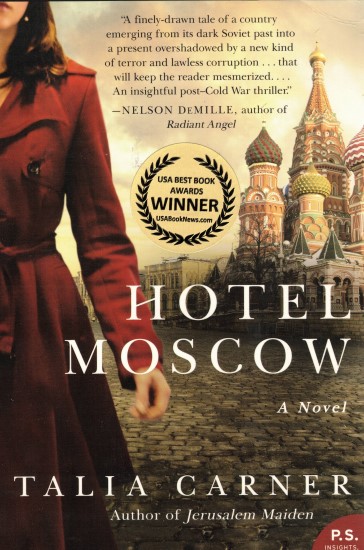

- An excellent interview by best-selling author, Lucette Lagnado (“The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit,”) at the back of HOTEL MOSCOW– both in print and in digital formats.

Background of HOTEL MOSCOW:

Q: When did you start writing the novel?

A: On November 3rd, 1993, three weeks after my escape from Russia—my second trip in six months—I had lunch with a friend who was a newspaper editor. I handed her the twenty-three page report I had written for the U.S. Information Agency that had sent me to Russia to teach business skills, and I said, “All it needs is hot sex and I have a novel.” She smiled. “Why don’t you write it?” Upon returning to my office, I canceled my afternoon meetings, and at 2:48 PM began my writing career. I never looked back.

Q: How has the novel evolved?

A: Obviously, the draft I wrote in 1993 was a maiden effort. Although I had been a voracious reader and possessed strong language skills, I had no idea how to structure a novel. I had not even begun to learn the craft of scenes, characterization, pacing and dialogue, or how to build tension with every paragraph. But I had a story to tell, and I did not let my fingers rest until, nine months later, I had a hefty tome of 640 pages.

Q: All this while running a successful marketing consulting firm for Fortune 500 companies and managing five offices?

A: Within three weeks of writing I knew that I had found a new calling. I told my husband that I wished to be “a kept woman,” and he immediately agreed. (Probably, for the first time since he’d met me, I would be staying put rather than traveling every week to Chicago, Memphis, Los Angeles or Detroit.) Since it was December, I declined to renew most client contracts for the following year, closed my firm’s satellite offices, canceled four out of my five phone lines, and donated my suits to charity. Prior commitments to clients were executed for the next eighteen months by a skeleton staff while I continued to write feverishly. The last business check I received was from Lincoln Mercury in July 1995.

Talia in Mosocw during the 1993 uprising (The deserted Red Square and the Kremlin in the far background.)

Q: Now that you had this thick draft, what did you do?

A: The internet was just starting to spread, and I discovered that there were about six hundred writers’ conferences and workshops each year in the US. For a few years I became a conference junkie, traveling from one program to another, studying, working with editors and creating a network of writing buddies. (So much for my husband’s hope that I would be home 24/7….) I read “how-to” books about the craft of writing fiction and joined excellent writing groups, both online and face-to-face. With plenty of feedback and lessons learned, I revised and rewrote the novel numerous times.

Q: How did you gather the material you wrote about?

A: That novel—never published—was focused on Russian women and their lives. I conducted many interviews with Russians who had emigrated to the United States just before and had fresh impressions of the trials and tribulations of living at the bottom of the food chain in a corrupted society. I also attended lectures about the Russian politics of the time, and interviewed Cold War-era US security personnel. Personally, while visiting Russia twice in 1993, I watched these women—probably the most educated group I had ever met—suffer the indignation that came from deprivation: the famous food lines leading to empty stores and absence of basic consumer products since many had never been manufactured. Soviet Russia had been a superpower that cynically manipulated its people, toyed with their sense of worth, and deprived them of everything they wanted. The women were reduced to being gatherers and hunters almost like the African women I had counseled before.

Q: Indeed, the texture of Russia is so well described in your novel. The living conditions seem very authentic.

A: In Moscow and St. Petersburg I had visited small apartments, similar to the one described in HOTEL MOSCOW as Olga’s. But upon escaping Moscow in October 1993, at the Frankfurt airport, I met two American architects who had been hired by newly rich Russians to renovate old mansions that had been turned during Soviet years into ant-hills of rooms barely suitable for humans. I saw pictures of families–sometimes even three generations: an ageing parent, a young couple, and a baby–squeezed into a 10’ x 14’ space. Soon, I learned how common these communal apartments were both through my interviews and my continuous involvement with Russian women helped by the Alliance of Russian and American Women—the organization with which I had visited Russia the first time and which built a “business incubator” in St. Petersburg. One of our recipients had been a woman who grew mushrooms under the small table in her room; another had had to remove her sleeping cot to make room for a sewing machine. ARAW offered a facility for their ventures.

Q: What touched you most in regards to the status of Russian women?

A: Russia in Soviet times—and probably still now merely twenty years later—is a society of women heads of household with men gone MIA due to the malaise of alcohol. The Russian man’s life expectancy was only 57 years! (It’s 58 now.) Besides struggling politically to regain the rights they lost when the entire legal system was obliterated upon the fall of communism—medical care, school lunches for children, political representation in the parliament—women must deal with blatant sexual harassment. My fellow Americans and I watched powerlessly as officials and men of authority pounced on the women we counseled. In fact, a few times we, too, were pounced upon, literally, by passing strangers. Ads for secretaries require “long legs, no inhibitions.” I wanted to capture this intolerable reality in my novel.

Q: Nevertheless, HOTEL MOSCOW wasn’t published until now.

A: My agent in 1996 retired within six weeks after I had signed up with her, leaving that first novel an orphan. By then I had begun to research and write PUPPET CHILD, and as is the case with each of my novels, I fell in love with the protagonist, became engrossed in the new subject, and immersed myself in it for some years. Also, my visit to the International Women’s Conference in Beijing in 1995 had planted the seeds for the next novel, set in China. When CHINA DOLL moved to the publishing pipeline, I became excited about writing JERUSALEM MAIDEN and didn’t even plan to turn back to what became HOTEL MOSCOW until I sent my protagonist to Russia.

Q: How different is this version from the one you put aside in 1996?

A: Actually it is an entirely different story, as it stemmed from my fascination with a Jewish-American protagonist and her identity issues. I wanted to explore the character of Brooke Fielding, a young, urban, career-oriented Jewish Liberal who’s been trying to escape the legacy of her parents’ suffering during the Holocaust. I wanted to juxtapose her feelings against the reality of unabashed anti-Semitism. One day it occurred to me that if I sent her to Russia, it would be a fascinating journey of discovery for her. I was curious how she would react to the people and the events. I had done all the research needed for such a realistic situation. Using the material buried in drawers (the old draft had been written in DOS and could no longer be accessed,) I crossed Brooke’s path with the setting of Moscow during the uprising of the Russian parliament against then-president, Boris Yeltsin. Brooke is shocked to discover that in this civil violent clash instigated by the Russian president, the Jews are being blamed, yet again, as they have been for centuries for issues that have nothing to do with them!

Q: Do you identify with Brooke’s struggle with her Jewish identity?

A: Having grown up in Israel, in a secular family and culture, being Jewish is as strong an identity for me as being a woman. I never question it. However, while my family history is rooted two-hundred years in Israel, I grew up as the generation after the Holocaust with the mission “to remember.” At age ten my class trip was to a nascent Holocaust museum where we were shown lampshades made out of Jewish skin, and soap made out of Jewish fat. The older I became, the less I understood the horror of the Holocaust, until I could take the pain no more. I was “Holocausted-out.” Then, because of my decades-long involvement with American Jewish organizations, I began to wonder what it meant for a secular Jewish American to be a Jew.

Q: Even though you had already done most of the research, it took you a long time to write this version.

A: Almost four years. Writing HOTEL MOSCOW basically from scratch was a down-time project while I waited for JERUSALEM MAIDEN to get published, and then spent two years book touring for JERUSALEM MAIDEN, giving keynote speeches, chatting with book groups, blogging and doing media interviews. Even though I am now a much more experienced novelist, I still edit and rewrite almost non-stop. It is no exaggeration to say that I reread this version forty times. Luckily, I enjoy the process. With every round of editing I feel better about way the book is shaping up. I also rely heavily on feedback from fellow writers, which means that I reciprocate by being involved in their projects as well. In addition, I have also changed my writing routine from ten-to-sixteen hours a day, six days a week, to being more present in my real-world life—family, friends, travel, theater and charity work.

Q: What was the challenge in writing this novel?

A: Each of the protagonists in my previous novels was instantaneously sympathetic. In JERUSALEM MAIDEN, for example, the reader immediately feels for a twelve-year old who is supposed to be married off soon… . And I had no problem evoking compassion for the Russian women secondary characters in HOTEL MOSCOW. But how do I make the plight of a thirty-eight year old successful New Yorker empathy-worthy? How do I set up the story so that the reader would want to get on the journey with her? I knew where I needed to go—into the psyche of a second-generation Holocaust survivor who lived the experiences and the trauma as her own, whose existence to her parents was merely as a stand-in for all the children and relatives who had died. I struggled with how much of Brooke’s background to lay out and how much to let the reader extrapolate on her own. When my editor at HarperCollins told me how lonely Brooke seemed to her, I knew that I had nailed the character.

Q: You are seventh-generation Sabra (Israeli born,) yet once again you capture so well characters whose lives and experiences are vastly different from yours, be it a second-generation Holocaust survivor or Russian women.

A: I grew up with many Second-Generation children. Most of my childhood friends had parents who had survived the degredations and losses of the war, then crawled out of the ashes and created a second family, with only one child who rarely had grandparents, aunts, uncles, or cousins. My friends’ parents were all a decade older than mine and spoke German, Czech, Polish, Russian or Hungarian at home. My short story about it, Empty Chairs, received literary praise. As an adult living here, I talked with many American Jews who are Second-Generation. Because of my Israeli roots, they volunteer to tell me what they often keep bottled up: that their parents’ agony is never far from their minds and hearts; it forever accompanies them like a bubble of air they are breathing. They feel tremendous responsibility—either to remember, or to achieve, to be attentive to their parents, or to be upstanding citizens—that is uniquely related to the Holocaust. As for the Russian women, I had met, interviewed and befriended many in Russia, Israel and New York, and they reminded me of the valiant women of my own family…. In Russia, I felt an incredible bond with them across the language barrier. Their food was familiar to me (the staple appetizer at the cafeteria at the Hebrew university was half a boiled egg swimming in mayonnaise and surrounded by some peas,) and in my youth I danced the hora to Russian songs that had been translated to Hebrew(!) When we couldn’t speak, we hugged.

Q: And then there are the detailed days of the uprising of the Russian parliament against then-president Boris Yeltsin. Tell us about your experiences—and the escape.

A: Actually I witnessed some of the uprising: the violence in the street, the military confrontation, the tanks rolling into the city, and the burning of the parliament building. The event in which Brooke is caught in Hotel Moscow is quite literally what happened to me, with the difference being that after paying a lot of money, I hid in someone’s room, while my Congressman and my husband kept vigil by phone throughout the night…. The next morning I sneaked out the hotel—and the militia—without my luggage. I hid in plain sight at one of our conferences, when I learned that the American Embassy had reopened, but my handlers had kept this information from me, probably with an eye for more bribe for their “protection.” I hailed a private car and was lucky that the man who stopped accepted my $5 to drive me there. My USIA liaison at the Embassy put me up in a Western hotel for the night, sent someone to retrieve my luggage, and the next morning whisked me out of the country on the first flight.

Q: How relevant is HOTEL MOSCOW?

A: Russia is in the news every day. It is still in transition from the Soviet era—and some say that the current state of things doesn’t look like it has moved far enough to create a democracy and an open market economy as we know it. It took the Israelites forty years in the desert until God was convinced that the generation born to slavery had died. There may be wisdom to this notion of a people growing up in freedom in order to be ready for it.

Q: What’s next?

A: There is no greater pleasure for an author than to share her work with appreciative audience. I look forward to connect with readers through book groups and my speaking engagements.