(This essay appears in the back of the novel as “Author’s Note”.)

In May 2018, I visited the Clandestine Immigration and Naval Museum in Haifa in the company of Admiral (ret.) Hadar Kimche. The year before, I conducted extensive interviews with this modest then-eighty-nine-year-old commander of the legendary story of the Boats of Cherbourg. Hadar (who asked me to address him by his first name), then introduced me to over a dozen officers who had been involved in the breakout. On this 2018 Haifa visit, he took me to view one of the twelve missile-carrying boats Saars that had caused an international crisis in 1969 and four years later brought Israel naval victories in the Yom Kippur War.

I had not anticipated how the mere name of the museum would affect me, a reminder of the tight connection between the clandestine immigration to Palestine before the State of Israel was established in 1948 and the Israeli navy that was created upon the country’s birth. Four aging, barely floating vessels that had been refurbished after the Holocaust to transport thousands of Jewish survivors from Europe to the Promised Land were once again pressed into service, this time for the nascent Israeli navy.

Having grown up in Israel as part of its first generation, I had been fed detailed accounts of the clandestine immigration—Jews entering the country illegally because the British, who had been given a mandate in 1922 by the League of Nations (the precursor to the United Nations) to administer the land for the purpose of creating a home for the Jews, had reneged on the directive. Not only had they handed 76 percent of the Jewish-designated land to the Hashemites (creating Jordan), but in the wake of the Holocaust—when over three million displaced Jewish survivors who had escaped the Nazis had no place to go—Britain blocked the Jews’ entry to the remaining 24 percent of the land they had named Palestine.

Both this gross injustice and the heroism of the thousands who defied the British blockade was infused into my DNA, as were the horrors of the genocide of six million Jews that preceded it.

In 1969, twenty-one years after Israel was born, the astounding breakout of the Boats of Cherbourg dominated international headlines. The boats, all commissioned, designed, and paid for by Israel, had been built in a private French shipyard in a Normandy port, but their delivery was blocked due to a new French arms embargo on Israel. Two years later, in 1971, I learned that a small project I worked on while serving in the Israel Defense Forces had played a minuscule part in the vision, daring, and flawless execution of the boats’ escape.

Twenty years later, the Israeli navy revealed the identity of the person who had executed this heroic operation: Admiral Hadar Kimche.

What I instantly noticed on this visit, as I read the museum’s full name through the prism and wisdom of the passing five decades, was how all of these events—the Holocaust in Europe, the clandestine immigration to Palestine, and the escape of the Boats of Cherbourg—were interwoven and how close, timewise, they had been. In the spectrum of human history, and even in the shorter arc of the Jews’ exile for two thousand years from their homeland, these three time stamps occurred in the span of less than thirty years. Only the blink of an eye.

And then I read the inscription at the museum entrance, and the significance of history came rushing in, like a tidal wave:

though your footprints were not seen.

—Psalm 77:19

Even on land, history’s footprints often disappear just as quickly as if they were marked on water—and more so as the globe entered yet another century.

In the context of the clandestine immigration, there was a human-interest story that had touched me deeply but seemed to not have been fully explored:

While growing up in Tel Aviv, I occasionally encountered Holocaust orphans who had been saved by Youth Aliyah. All older than me, they had been absorbed in youth villages or kibbutzim or were brought to Israel by surviving relatives. Such was my friend David’s adopted older brother, a nameless five-year-old who was handed to David’s father by a monk. Since no one had come to claim this boy, the monk asked, would this Jew take him?

Such was Charlotte, who, at age four, was saved by a Red Cross nurse from Vel d’Hiv (where the Jews of Paris had been rounded and deported to Auschwitz)—only to be removed from that second mother’s home at age eight by an organization that placed her in a Jewish orphanage. Such was Miriam, who had been baptized by the time her Jewish father returned. When the twelve-year-old refused to leave her new family, he kidnapped her and took her to Palestine, where her distraught mother, who had lost two other children, waited. And such was Jacob, who for years labored on the farm of his Christian rescuers, abused and starving, receiving no schooling or medical care, until he was bought with cash by a Youth Aliyah agent.

There are as many unique, heartbreaking stories as there are children who survived. I did not want to tell another Holocaust story but rather to explore what happened afterward. How were these lost children found? Did an agent from the Jewish community in Palestine—the yishuv—knock on the door of every farmhouse and ask whether, by any chance, there was a Jewish child he could take across the sea to a place where people spoke a language the child wouldn’t understand? Yet it happened, and in this novel I set out to explore not stories of trauma and loss, but that of a Youth Aliyah agent’s journey to heal these children’s scarred and broken hearts.

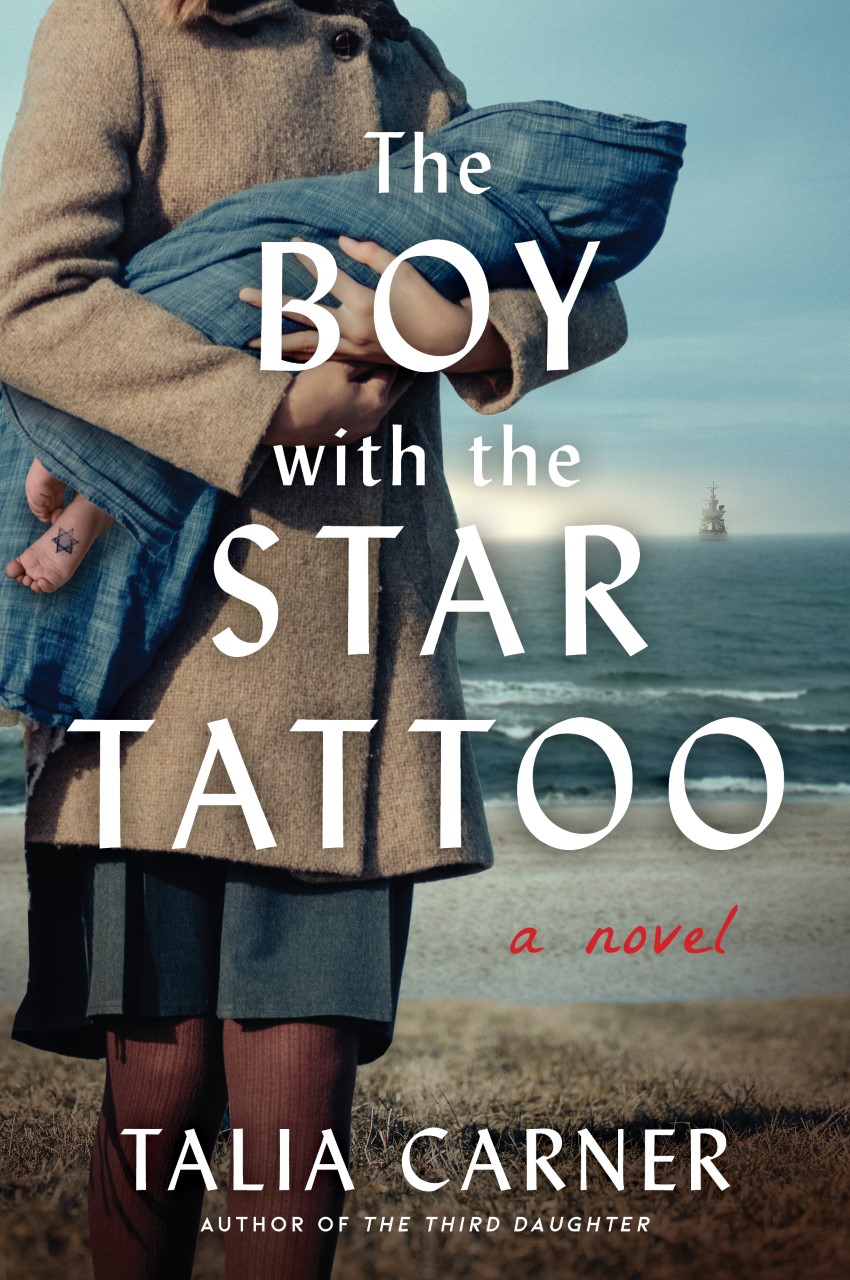

THE BOY WITH THE STAR TATTOO links all these events that have dwelled in my psyche. Each episode in this extraordinary historical saga stands on its own. Woven together, they create a story of the resilience and fortitude of the Jews who reasserted their right to self-determination in their own homeland. Without Israel, we Jews would have been the Kurds and Romani of the world—landless, oppressed, disrespected, and exploited. Israel continues to offer refuge to Jews whenever the need arises, and thanks to that security, along with the nation’s achievements in science, technology, and medicine, Jews everywhere can walk tall. We belong.

Talia Carner, January2024

For more about The Boats of Cherbourg, please click.