Additional written interviews:

Background of THE THIRD DAUGHTER:

Q: How were you exposed to the topic of trafficking?

A: I had first heard about it at the 1995 International Women’s Conference in Beijing. I listened to testimonies of aging Filipinas, Korean and Chinese women about their enslavement by the Imperial Japanese Army during WWII, when, all throughout the Pacific Rim, Japanese soldiers captured tens of thousands of women and placed them in “comfort stations” to serve the sexual needs of the Imperial Japanese Army.

The plight of kidnapped women forced into sexual slavery stayed with me in subsequent years, and I found myself reading about it and attending in New York presentations by UN-affiliated NGO’s.

(At that conference I also learned of other forms of violence against women—abuse of molested children in the USA by our legal system, and in China, the singling out of baby girls for death. Both issues ended in my penning my first and second novels, PUPPET CHILD and CHINA DOLL.)

Q: What’s the story behind the story of THE THIRD DAUGHTER?

A: I was also vaguely disturbed by old account of Jewish sex trafficking in Argentina. In 2007, on my third trip to Buenos Aires, I visited the new AMIA, the imposing building that housed all Jewish organizations (after the previous one had been bombed in 1994, killing many.) I ambled into the library, where I chatted in English with the librarian. However, when I asked her casually about “the Jewish prostitutes and pimps,” she suddenly forgot her English. I understood that I had stumbled upon a shameful chapter in the history of Argentine Jews.

Eventually I searched for information about Zwi Migdal and was astonished at how much was available on the internet in English (plus a lot more in Spanish,) about this organized Jewish pimps’ union headquartered in Buenos Aires, and which had operated with impunity all over South America and beyond for 70 years until WWII.

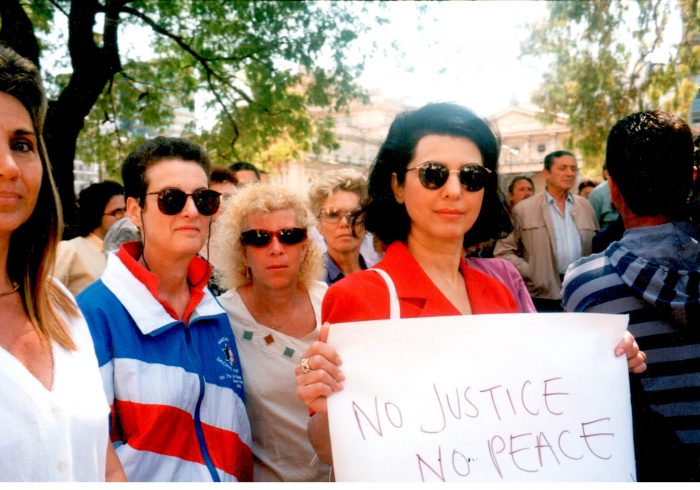

1996 Buenos Aires: Talia Carner at a demonstration in front of the Argentine Department of Justice, demanding the investigation of the 1994 AMIA bombing.

Q: What’s the connection to Sholem Aleichem’s short story?

A: Published in 1909 by the Yiddish-language author of hundreds of short stories, The Man From Buenos Aires describes the shady, sleek character who brags about his business acumen and his riches but never reveals to the author in what kind of enterprise he is actually engaged. As intended, this character leaves the reader with unease….

When I ordered the story collection in both English and Hebrew where this story was republished, I was surprised to learn that the collection, titled “The Railroad Stories,” also included the stories about the memorable Tevye the Dairyman, best known in the adaptation to Fiddler On The Roof. The author had structured the stories as if, during his train travels, he met different people and heard their stories. Tevye showed up time and again to report about the next episode in his family life.

I always thought that Jewish shtetel life, so steeped with strife, poverty and pogroms, was sugar-coated in the various theater and film adaptations. Life for the Jews had been far worst under the czar’s incessant edicts and bloody pogroms. My imagination was fired at the thought of what would have happened if, after fleeing a pogrom, one of Tevye’s unmarried daughters met that shady man from Buenos Aires?

Q: Yet Sholem Aleichem already tells the story of his third daughter.

A: That’s when inspiration takes over and gives a novel a life of its own. In fact, when Tevye first tells the author about his daughters, he says he has seven, then six, and at the end recounts only the stories of five daughters. Had THE THIRD DAUGHTER been the never-told story of the sixth, it would have required the retelling all the sisters’ tales. In fiction, all characters must serve the story line, and superfluous sisters would have had no impact on the events that were to unfold. Instead, I let my imagination run loose, changed the names and circumstances, and set on the journey with Batya. I let her take me to another place, with a completely fresh plot.

Q: What was the creative process that led to her story?

A: In 2015, while I was on book tour for HOTEL MOSCOW, a casual remark by a reader about the “Comfort women” jolted me anew. I began to research and write about the Japanese sexual enslavement of women during WWII.

I was about 50 pages into this novel when I happened to travel in December 2015 to Santiago, Chile, for the Maccabiah Pan-Am Games. I brought with me Isabel Vincent’s book “Bodies and Souls: The Tragic Plight of Three Jewish Women Forced into Prostitution in the Americas.” My intention was to read it and discuss the topic with my many Jewish South American friends. However, the more I immersed myself in Vincent’s excellent investigative research, the more I grasped that perhaps just one or two generations ago any of my friends might have been connected to the pimps or prostitutes.

Back home, as I was plowing through my Japanese enslavement story, the voices of the victims of Zwi Migdal whispered in my head. I tried twisting away from them, since I never wanted to write anything bad about Jews, and both my husband and I worried about offending our Jewish South American friends. But then the whispers turned into cries demanding I tell their truth, and a weird subplot about a Jewish woman lured from Russia to South America under a false promise wove itself into the Japanese enslavement story. Before long, it pushed itself to the forefront of my computer screen….

I finally gave in. I submitted to wherever the creative process would take me without trying to force it into another orbit. I closed my eyes, and, with my fingers on the keyboard, let myself be swept with the protagonist across the ocean from a Russian shtetl to South America. I let myself crawl under her skin, suffer with her, rise up with her bravery and drop into the abyss with her despair. I suffered her humiliation when she and her friends were shunned by the “virtuous” Jews. I lived her doubts and the moral dilemmas she faced—and basked in the comfort of new friendships and exhilaration in her joy of tango.

Q: What has been your greatest surprise about the release of the book?

A: In the months leading up to publishing date, I found out that literally no one knew about Zwi Migdal. I even asked people knowledgeable in English-language Jewish literature whether they’d come across any work of fiction about the subject, and although there is plenty of non-fiction English documentation of that traffickers’ organization, none had ever even heard of it. Everyone was shocked to learn of the tragic fates of what I had by then discovered were about 150,000 to 220,000 Jewish girls and women who worked as prostitutes, not counting the thousands who committed suicide.

Q: Your mother’s painting has played a role in this creative process. Tell us about it.

A: My late mother, who passed in 2012, was a fabulous artist. My favorite oil painting of hers is of a Spanish-looking, well-dressed couple. Her skimpy dress and his demeanor as he reaches for her, while her head is leaning away so far that her neck almost pops out of her shoulders, show the dynamic of that relationship. I often stared at the painting, touching the canvas where I knew my mother’s fingers had been and recalling that she always remembered every brush stroke…. My mother referred to the painting as “The Tango Dancers,” but one day, as I was touching the painting, it dawned on me they were not dancing, that this couple’s story was connected directly to the novel I was so resisting to write. It was telling me the story of my protagonist! Neither my mother nor I believed in other-worldly messages, but I nevertheless took it as a sign. I know that she would have been enormously proud that her painting inspired me to tell the story of the characters she must have so profoundly understood.

Reviva Yoffé’s painting, “The Tango Dancers”

Q: What do you hope to accomplish with the publication of THE THIRD DAUGHTER?

A: Two things. First, while I can’t make up to the women and girls victims of Zwi Migdal for being betrayed by our people—no charity would help the tme’ot, the impure, once they were caught in the net, and the upstanding Jews even refused to bury them in the Jewish cemetery. But I can make up to them for having been forgotten. I can tell their truth.

Second, through the protagonist, Batya, I would like the readers to see the humanity of the prostitutes. Regardless of how they act and what they say, they are victims. In the USA, the vast majority of them has a painful history of sexual abuse, homelessness and foster care. They are victims of our decades-long neglect. Those who come from other countries are most like been duped and kidnapped. I would like to use the novel as a platform for a call to action against the trafficking that is, sadly, as bad today as it was 120 years ago.

Q: Are you taking up a fight against prostitution?

A: I have been in touch with an organization of female sex workers who freely choose this profession out of other employment and lifestyle options open to them in the USA. I must respect their sense of independence and their right to make educated choices. This is entirely different from the enslavement of women lured with lies, who are captured, beaten and locked up, then forced into sexual subjugation. Human trafficking and slavery is never okay, and I welcome the opportunity to inform my readers, both via my website and in my keynote speeches about ways that they can fight this evil in their own backyard.